Although asking literary agents and book publishers to pick your work is a huge part of the writing life, I avoided it for a long time. Over the years, publishers accepted articles I’ve written. Blog hosts published my guest posts. I have published books that other people have written, as well as one that I wrote. I have helped other authors set up their books via their own indie publishing enterprise. I have contributed chapters to published books edited by others. Until recently, though, I hadn’t asked someone else to publish a book that I wrote.

It’s a whole new adventure. Do people enjoy asking strangers to stop, look, read, and love their manuscript? Perhaps. I’m not aware of anyone who reports a fondness for the activity. The conventional wisdom is that querying, as this process is called, is a necessary slog. It can take years of querying one manuscript before an opening appears, and more years – if everything goes well – before that manuscript emerges in print as a new book. Writers swap stories of the long road from query to publication. They curse the agents who turn them down, and then they sometimes curse the agent(s) who work with them.

Agents

Agents also struggle. There’s never enough time. They work on commission, earning money from a manuscript only after they’ve managed to sell it to a publisher. They earn more money when that book becomes successful in the marketplace. This provides incentive to pick winners, not just projects of which they are fond. There’s also the dream of picking the unknown project that becomes the next big thing. But that’s much riskier.

Agents’ time needs to be allocated to growing and strengthening their network of connections to the acquisitions editors at every publishing house and imprint that might one day be a fit for one of their clients. (If you already know them, you have a much greater chance of getting them to agree to take a look at a new project.) But agents’ time also needs to be allocated to working alongside their existing writer clients, negotiating film rights, working with the audiobook narrator, conferring on – if not always able to approve – the cover design of their clients’ next books. But their time also needs to be allocated to reading the new stuff that’s perpetually coming in via new queries from new authors. Most literary agents got into the business because they love reading. From what I hear, though, a busy agent barely has time to think, let alone sit down with a new manuscript from an unknown author.

The lottery

Why do unknown novelists like me even bother? If the system is rigged against the new writer, what’s the reason for slogging away, against the odds, hoping to be the exception? Because deep down we each believe our work is special. Because it’s a rite of passage. Because if you don’t buy the ticket you can’t win the lottery.

You gotta be in it to win it.

Photo by José Pablo Domínguez on Unsplash

Sometimes it feels as though querying is like buying a ticket and then paying interest on the ticket price. Your carefully polished query letter is the price of the ticket. Rejections are the interest. Stories abound of writers who papered the walls of their room with rejection letters – back when correspondence happened on paper. For a while, I’m told, agents sent replies to querying authors via email, usually in a standard rejection that a lowly office assistant or automated process could issue, occasionally with a more carefully worded note. (I have celebrated heartily with friends who exclaimed, “I got a personalized rejection!”.) Nowadays, many agents explain in their submission guidelines that not hearing from them after a period of time means the query has been rejected.

I knew of one unpublished novelist who didn’t go with the subservient flow. She was an experienced radio journalist, who knew her way around a sentence, and had name recognition among the NPR cognoscenti. When it came time to query her novel, she donned the mantel of a professional, not a supplicant. It worked! She treated the agents as peers, and they responded in kind. She got a modest book deal, and her novel was published to some critical acclaim. This was several years ago now, and the querying process has only gotten more difficult since, but her example still shines for me like a beacon.

Andie Jordan

What am I querying? A novel – my first – about Andie Jordan, a young woman finding her way in the New York City art world of the early 1980s.

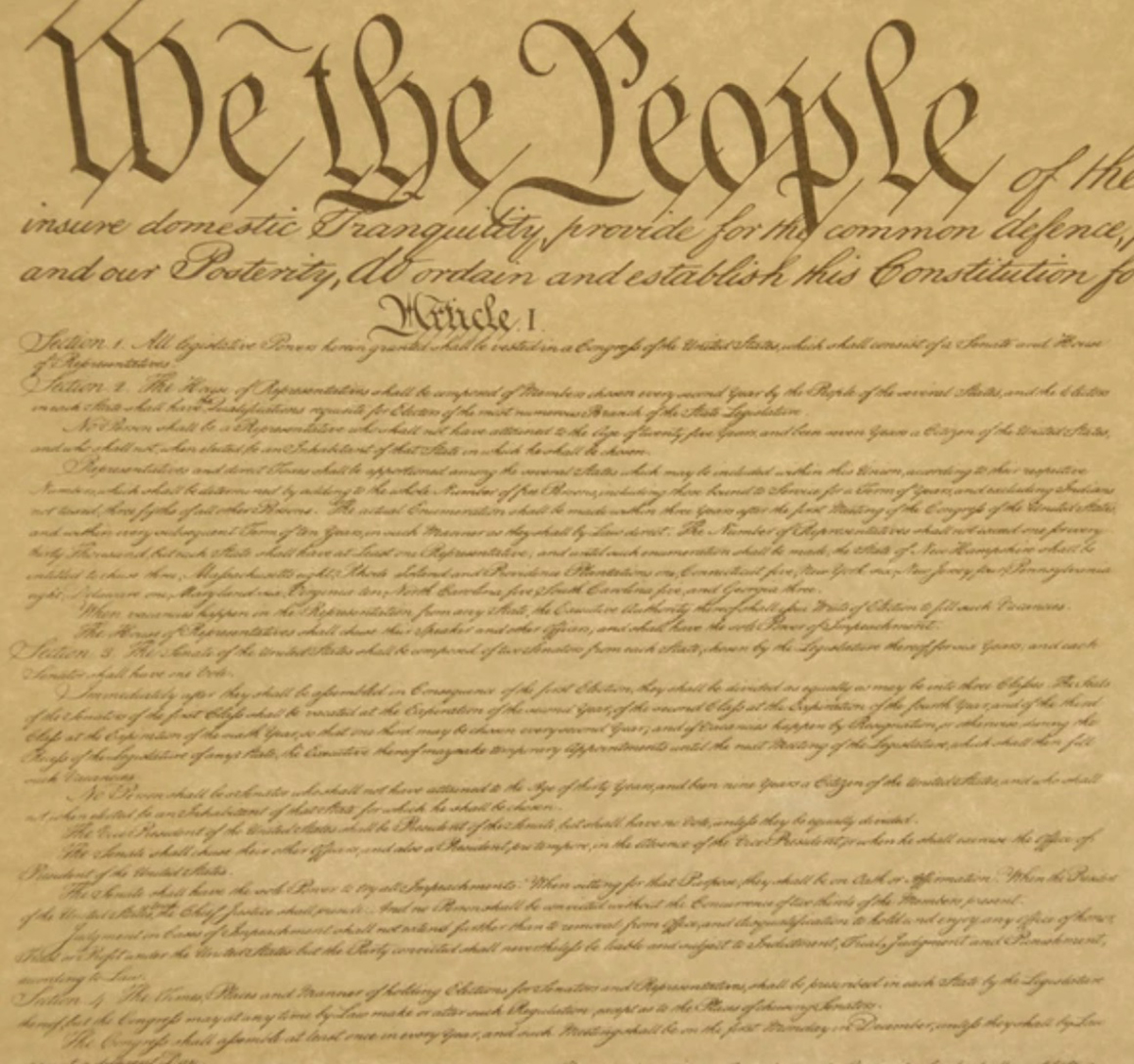

Who am I querying? Some agents and some small publishers. From what I can tell, books like mine are slightly more welcome at certain small presses than they’d be at the big corporate publishing houses. As the PRH / Simon & Schuster news last fall indicated, the big five are publicly traded companies responsible to shareholders for profiting from books and other intellectual property. They prefer proven winners – in the form of (already) best-selling authors, popular tropes, celebrities, pop-culture heroes, and themes ripped from the headlines. “Quiet” novels like mine – and I mean that as a compliment – aren’t likely to be their cup of tea. So whether I look for an agent or a publisher, the publisher that would bet on my book is almost certain to be a smaller one.

How am I querying? I write (and rewrite) a query letter. This is a one-page term paper / marketing document that must obey certain guidelines. Some of these guidelines, available online, are specific to each agent or publisher. For example, the periods of time when they are, or will next be, open to queries; the form in which they accept queries – in the body of the email, or attached to an email in 12-point Times New Roman with one-inch margins – or the kinds of projects they want. Others are generally accepted industry standards, like including your book’s title, word count, genre and category, plot, and author bio. Writing and rewriting your query letter is a part-time job, as is updating your research on agents’ and publishers’ open dates, submission rules, schedules, wishlists, and more.

Want to see my “plot paragraph” – the heart of the query letter? Here you go:

Andie Jordan is a talented painter and aspiring writer in 1980s Manhattan. A manager at the cutting-edge New Art Center, she tirelessly supports the arcane artistic visions of a select group of middle-aged white guys – until the job completely takes over her life and she stops painting. Even after she resigns, the Center pulls her in. While she struggles to recover from workaholic burnout, a federal prosecutor questions her in his case against the Center for mishandling public funds. A work friend has a debilitating breakdown; looking into its cause embroils Andie further in Center business. Desperate to leave arts administration behind, she enters journalism grad school, with plans to investigate the intersections of art and money. Her thesis advisor, with secret ties to the Center, criticizes Andie’s tactics. The prosecutor discourages her research, which might jeopardize his case against the Center. Then, out of town to exhibit some new paintings, Andie learns that her ex-boss, who can blackball her from New York galleries, wants her added as a defendant in the criminal case. She despairs of ever breaking free from the Center’s long reach to clear an independent creative path.

#amquerying

I maintain a spreadsheet of agents and small publishers whose expressed interests intersect with what my novel can offer them. So far, everyone I’ve contacted has either said no or has said nothing.

My novel’s working title is Andie Jordan Needs a Life. Why “working title”? Because in the unlikely event Andie gets picked up, a lot will be subject to change, including the title. When it comes to book marketing, everyone knows that we DO judge a book by its cover, as well as by its title (a significant element of said cover). And the publisher of a first-time novelist will have a lot of power and influence – earned over years of experience and marketplace clout – over the debut author. So titles often change. I’ve already changed Andie’s title several times, on my own, and remain open to better ideas.

Will I stop the madness? Very likely. But not yet. I feel as though playing this out is teaching me things I need to understand. I’m learning by doing. I have joined the immense community of writers who dedicate themselves to the process of querying. On a good day, I can feel us cheering one another on. Go, fellow queriers!

— A M Carley writes fiction and nonfiction, and is a founding member of BACCA. Through Anne Carley Creative she provides creative coaching and full-service editing to writers and other creative people. Decks of her 52 FLOAT Cards for Writers are available from Amazon. Anne’s writer handbook, FLOAT • Becoming Unstuck for Writers, is available for purchase from central Virginia booksellers, at Bookshop.org, and on Amazon. She’s querying her first novel, and writing her second.