Writers need help to be our best. We need careful readers with sharp, unwearied eyes looking at our work, shining the light of what they know on what we’ve written. We might prefer to avoid it, but in the quest for excellence, a little aid is absolutely necessary. So…

How do you find (and give) helpful help?

How do you create an environment where respectful and rigorous critique is possible?

What are the essential elements of a beneficial critique?

The members of BACCA have been thinking and talking about this lately. We’ve put our heads together and gathered some of our thoughts here. In my own thinking about these questions, I’ve uncovered a point of origin—an opening strategy I use when I approach the work of another writer.

Assume it’s there for a reason…

I begin with this: everything is intentional. I assume the writer has something in mind and figuring that out is my first job. Simple enough—but it goes against the grain. A book feels finished, complete, but it’s natural when handling a manuscript to assume that it’s flawed—it’s a draft, after all. But if I assume from the start that every surprise, every unfamiliar turn is a flaw and not a carefully chosen move, I miss an opportunity—a chance to learn something, to see from a new perspective.

After enduring disappointing critique experiences of my own, I’ve learned that it’s best to identify a writer’s project before I do anything else. This summary becomes my north star as I spend time and get to know a manuscript, mapping out its tendencies, its borders, and its open ends.

Believing that every part of a manuscript is intentional, included for a specific purpose, doesn’t mean that there is nothing more for me to do and no way I can help. Useful comments are in conversation with the project summary I’ve identified. Positive comments highlight parts of the writing that support and enhance the goals of the project. Questions I have may indicate places could undermine or conflict with what I believe the writer is trying to do.

If you find yourself in unfamiliar territory…

It’s human nature to privilege the familiar. We like to know where we are and what kind of story we’re in. Roughly knowing what to expect—a series of predictable surprises—makes us comfortable. But, assuming that a draft needs to be remade to look familiar can cause real damage. I know this first hand.

In one graduate-level workshop, my writing was chewed up and spit out, over and over. Criticism is never fun, but some of the feedback I received in that class was legitimate and some of it was not. Some of it made me a better writer and some of it threw me off track. It took me a long time to sort out the constructive comments from the lazy, arrogant ones.

One student (I’ll call him Mark) indulged in what I now regard as a careless, irresponsible style of critique. Every time I submitted work, Mark would speak first, but he would always say the same thing:

I just don’t know where I am in this poem.

The comment itself seemed innocent enough. As a jumping off place for discussion, it might have been. But Mark, once lost, dismissed my poems entirely and refused to go further. If he didn’t know where he was in the poem, he assumed it must not be good. Inevitably, the rest of the class would follow his lead, even though I knew from their written comments that they’d had different reactions. Unfortunately, the facilitator of the class allowed him to dominate discussions of my work with this same comment, over and over. The indulgence helped no one in that room.

The problem with his comment, which he never realized and (to be fair) I never revealed to him, was that it was based on a false assumption: if he got lost in my poem, I had failed. But, it was never my project to locate him in a known place and time. If he had known where he was, I realized later, that would have been a failure. Mark’s poetry was full of trains and clocks and suburban sprawl—things I wanted to escape. I wanted to explore wildness, myth, and emotional rawness; I wanted to illuminate the edges between civilization and uncultivated territory.

Of course Mark didn’t know where he was!

Sadly, he was unwilling to push past the shock of being in unfamiliar terrain to discover the qualities of the world I was trying to create. So, we both missed a chance to learn from each other. If he had stretched his imagination past comfortable, if he’d thought to identify my project instead of just pointing out what it wasn’t, there might have been meaningful critique—which could have helped us both.

The best first gift…

Several artists I know—writers and painters and musicians—have told me that the most thrilling moment is to have someone encounter their work and really see it, to spend enough time with it to know it and really get it. Maybe this is the best first gift we can give each other in a meaningful critique. To say, yep, I see what you’re doing…

At the very least, it seems a decent place to start.

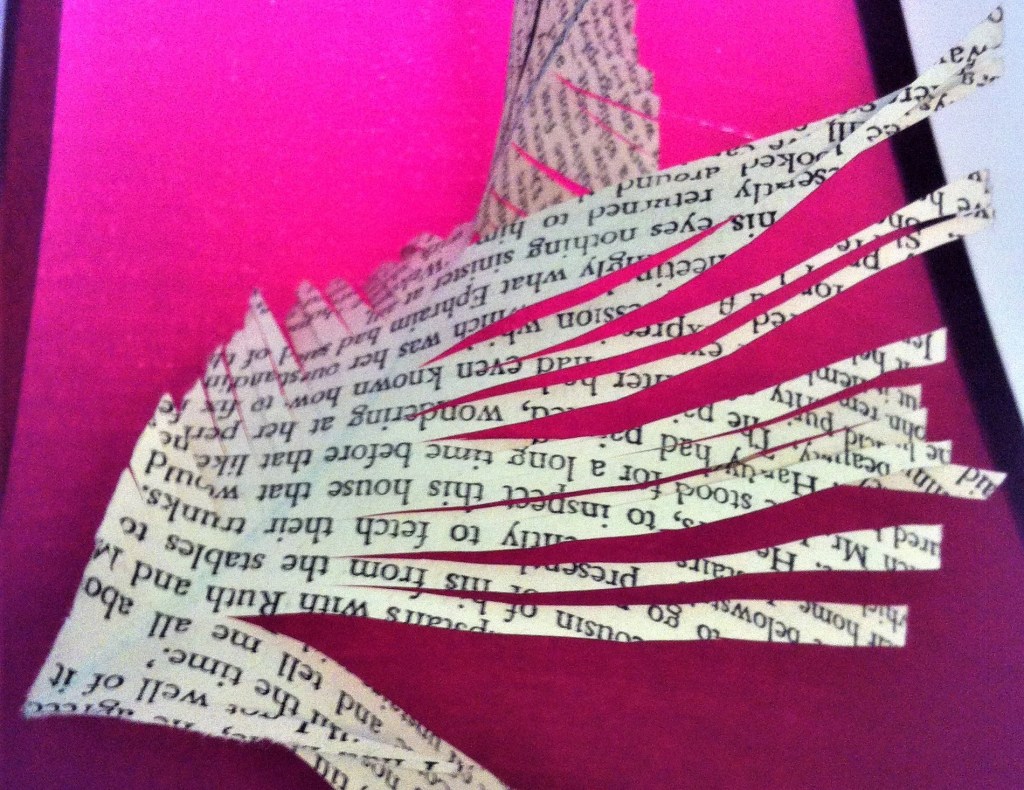

Noelle Beverly writes poetry and prose, promotes local writers in the surrounding community, and is a member of the BACCA Literary group. Photos by author.

3 replies on “Critiquing Critique”

[…] is dangerous business. Feedback, if carefully crafted and delivered, is essential for writers. However, thoughtful critique is a very different creature from carelessly formed criticism. Godzilla’s […]

[…] own Noelle Beverly put this evergreen blog post together a while ago for our website, after working on an internal document for our critique group. […]

[…] Her suggestions are thorough, generous, and deeply insightful. You may recall seeing Noelle’s blog post here about this recently, as […]